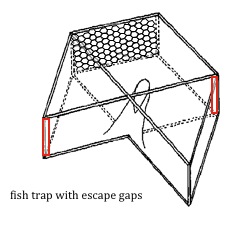

Solution: Escape Gaps for Fish Traps

Originally published on the (now archived) National Geographic blog.

May 7, 2013

Bycatch. That’s the fish that fishers didn’t mean to catch but did – baby fish, species people don’t like to eat, fish no one will buy. High levels of bycatch make fishing unsustainable, not to mention it’s a huge waste. So what can be done about it? Well, that depends on the type of fishing gear being used. For fish traps (often called fish pots), I have a solution: put a hole in the corner. No, I’m not being glib. Putting vertical, rectangular holes, aka escape gaps, in opposing corners of fish traps can reduce bycatch by up to 80%, without reducing (and potentially even increasing) the value of the catch. How, you ask? Escape gaps allow the narrow-bodied and juvenile fish (including lots of herbivores) to escape, while retaining the larger, meatier fish that fishers want to catch. It’s that simple.

For a delightful, colorful, and way more entertaining explanation, check out the animation by Odd Todd (above).

This was the first research project I did as part of my PhD dissertation. I designed these fish traps with a local fisherman in Curaçao (Thank you Ibi Zimmerman!), and then did hundreds of SCUBA dives to examine the catches of different trap designs … Tada! The escape gaps worked. Tim McClanahan of Wildlife Conservation Society tried them out in Kenya … Again! Worked like a charm. Want to see the data? Check out my full paper, and one by Tim and his colleagues will be published soon.

Figure 2 from Johnson et al. 2010. Mean (±SE) catch composition of trap sets for families representing 5% or more of the total catch of control traps.

Armed with evidence from both the Caribbean and Indian Oceans, we entered this sustainable fishing concept into the Solution Search competition sponsored by Rare and National Geographic. We won! (Sincere thanks again to all who voted for us. For more info: our entry and my blog post.) Commission of the video above (and here’s the Vimeo link) was part of the prize, along with funding for future research, and a lovely plaque that’s in my office. Since the award, I got consumed by other projects (such as the Barbuda Blue Halo Initiative that I’ve also been blogging about here), but Tim has continued to work to spread the adoption of escape gaps in additional communities in East Africa, and I’m hoping Barbuda will adopt the gaps too (one fisherman already has new traps designed).

Escape gaps are now required in all fish traps in Curaçao. In Kenya, one fishing community (Mkwiro) has adopted use of escape gaps, six additional communities are testing it out, and Tim is raising funds to spread this work to Tanzania, Zanzibar, and Dar es Salaam.

The majority of reef fish captured globally are caught in fish traps. Using escape gaps to increase the sustainability of trap use is simple, inexpensive, doesn’t require new gear, and it can work anywhere. Existing traps can be retrofit with a variety of low-cost materials, depending on what is available. As an added bonus, traps with escape gaps can reduce catch of key herbivores (i.e., parrotfish and surgeonfish) by over 50%. These algae eaters (I like to think of them as lawnmowers) are critical to maintaining coral dominance on reefs.

In sum, escape gaps are a win-win for fishermen and conservation. Fishers make the same or more money, while the fish population and ecosystem can rebound due to reduced catch of juveniles and herbivores. This, in turn, could further increase fishers’ incomes in the future when there could be more fish to catch.

Kenyan fishers lined up to receive escape gaps.

The problems facing the ocean can seem daunting, but in many cases they are also quite straightforward. Whether the issue is overfishing, climate change, pollution, or habitat destruction, we already have lots of solutions. The diagram below by Jennifer Jacquet and colleagues (full paper here) shows the full spectrum of solutions for overfishing. More solutions are of course always welcome, but we already have more than enough to start with: gear modification, marine reserves, ending subsidies for unsustainable fishing, community-based enforcement, etc., etc., etc.

So? What are we waiting for? Chose a problem, chose a solution, and go!

A message from your friendly Waitt Foundation Director of Science and Solutions. (Yes, that’s my official title.)